The possibility of exhibiting non-crystallographic rotational diffraction symmetry is restricted to quasicrystals because the other types of aperiodic crystals have periodic average structures. However IMPs and CCs can be seen, respectively, as incommensurate modulations and intergrowths of d-dimensional periodic structures (Janssen et al., 2018 ).

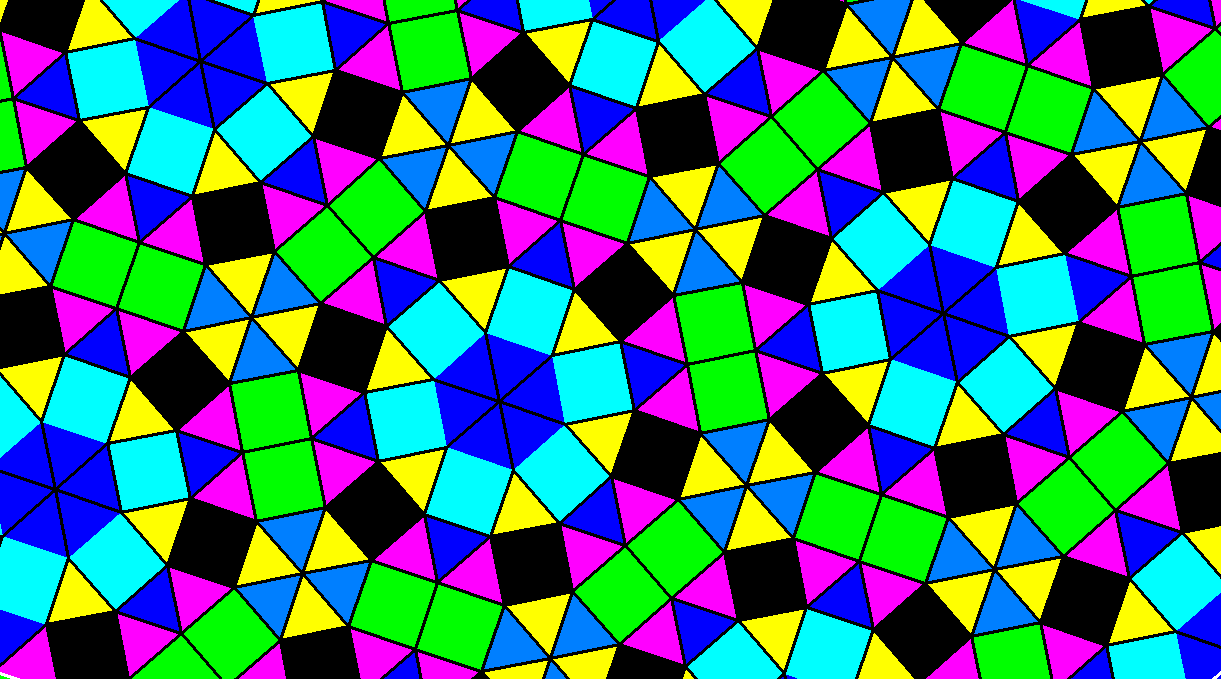

Quasicrystals are a type of `aperiodic crystals' along with incommensurately modulated phases (IMPs) and composite crystals (CCs). However, in the 1980s, the discovery of quasicrystals (Shechtman et al., 1984 ) broke the established paradigm as these intermetallic compounds can exhibit forbidden symmetries such as five-, eight-, ten- or 12-fold symmetry axes (Kortan et al., 1989 Fisher et al., 1999 ) and accordingly they exhibit diffraction patterns with Bragg peaks arranged with the same forbidden symmetries (Tsai & Cui, 2015 Maciá Barber, 2019 ). These restrictions are part of the well known crystallographic restriction theorem, closely related to Haüy's crystallographic `law of rationality' (Coxeter, 1973 ). 32 for 3D crystallographic point-group symmetry). Periodicity of common crystals implies that they can be generated by a list of independent finite translations, and this results in a finite number of allowed rotational symmetries (only two-, three-, four- and sixfold rotational symmetry is permitted) (Sharma, 1983 ) therefore the number of symmetry groups is also limited ( e.g. `a periodic array of atoms or group of atoms packed along the three space dimensions' Authier & Chapuis, 2017 ). Periodicity and unit cell are key concepts in crystallography and they were fundamental in the classical definition of a crystal ( i.e. Of the 47 peer-reviewed articles listed in a recent systematic review of 3D printing in chemistry education (Pernaa & Wiedmer, 2019 ), many deal with the production of physical models of molecular and crystal structures. As many of these concepts require capacity for abstraction and spatial vision, many educators are taking advantage of the rise of 3D-printing technologies to develop interactive haptic environments for education. Some undergraduate institutions have adapted the pedagogy of hands-on research to crystallography with the use of single-crystal desktop instruments (Crundwell et al., 1999 ), and many other affordable virtual (Arribas et al., 2014 ) and tangible resources are available as educational supporting material for a number of important concepts in crystallography (Gražulis et al., 2015, and references therein). Moreover, many physics, chemistry (Fanwick, 2007 Pett, 2010 ) and materials science graduate programmes also include introductory notes on crystallography (Borchardt-Ott, 2012 ). Crystallography and X-ray techniques are present in geology graduate programmes (Hluchy, 1999 ) as an independent topic or as a significant part of mineralogy courses. The aesthetic qualities of crystals, as well as the symmetry of their idealized representations and that of lattices, can grab the attention of students and motivate them to pursue further studies of the subject. Crystallography is sometimes present in innovative teaching tasks, including project-based learning, through experiments and competitions of crystal growth. Effective application of X-ray diffraction techniques in geology, solid-state chemistry and materials science requires a basic understanding of crystallography.įrom the academic point of view, crystallography is often present in secondary school chemistry courses through the study of crystal growth and sometimes as an accessory part within earth sciences courses (as part of mineralogy). Diffraction techniques are widely used to identify and ascertain the crystal structures of all kinds of solid substances, from organic to inorganic solids, pharmaceuticals, biological substances such as proteins and viruses etc. This led to the development of modern X-ray diffraction techniques and X-ray crystallography. In the early 20th century, soon after the discovery of X-rays (1895), diffraction of an X-ray beam by a crystal contributed simultaneously to revealing the nature of X-rays (electromagnetic waves) and to confirming the space-lattice hypothesis. Systematic study of crystal shapes led to enunciation of the law of the constancy of interfacial angles and soon it was argued that crystals must consist of ordered arrangements of atoms or molecules in a lattice (space-lattice hypothesis). Crystallography started in the 17th century as the science for the study of the external shapes of crystals.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)